Writing mysteries isn’t easy, but it can be rewarding. According to science fiction author David Brin (Writing Excuses podcast 7.10), all new writers should write a murder mystery for their first novel. His reasoning? The techniques you are forced to learn can be applied to any other genre.

Where should you start? Before you put fingers to keyboard, here are a few things to think about.

1. Explore the Mystery Genre

Readers expect certain elements when they read a particular genre. For example, in a romance they expect kissing, in a western they expect a horse or two, etc. In mysteries they are looking for a dead body — or at least some form of foul play. They also expect a sleuth or sleuths to try to figure out who did it and clues to point to the answer. It’s okay to shake up the expectations, but do it from the perspective of knowing the rules and breaking them rather than stumbling because you aren’t aware of the norms.

To see how the publishing industry defines different types of mystery novels, take a look at GoodReads. Some of the subcategories/subgenres may differ from those found in writing handbooks. For example, where writing guides may lump all mysteries with amateur sleuths into the cozy category, GoodReads lists Amateur Sleuth Mystery as separate from Cozy. This makes sense because although cozies always feature amateur sleuths, they also have other elements such as they take place in a small town and the level of violence is low to nonexistent. On the other hand, GoodReads combines private detectives and police detectives into Detective mysteries, whereas most writers consider mysteries featuring law enforcement sleuths as “police procedurals” and those with private detective main characters as their own subcategory.

In any case, the lists are wonderful places to find new novels in each genre and subgenre. Reading mystery novels in each category is a good way to learn about them. You can also see which novels are popular (1000s of reviews) and which are not (only a few reviews).

Items 2-4 may be done in any order, but they are tied to one another.

2. Pick a Great Setting

A good mystery answers the questions who (is telling the story), when and where early in the book. Both when and where are the setting.

Answering these questions right at the beginning helps orient the reader and gives information about what to expect. If the setting is a small town in Maine, expect a cozy. The story of a private detective living in New York or Los Angeles will probably be grittier. If the year is 1871, the reader is going to look for a historical mystery with details that fit the times.

If you plan to pen a series, consider how many dead bodies the citizens of your setting will realistically generate. For example, the Lewis series on PBS was set in Oxford, England with a population of about 150,000. The show portrayed numerous murders per episode over eight seasons, giving Oxford an abnormally high murder rate. Note: If you’re going to feature a particularly gruesome serial killer, tourism boards everywhere will thank you for creating a fictional city or town for your setting.

The setting will also influence who you choose as your sleuth, which is another reason to consider it early. J. A. Jance’s J. P. Beaumont series is about a homicide detective working in Seattle. Her Joanna Brady series, in contrast, is set in the small town of Bisbee, Arizona. In that setting, it is more appropriate for her main character to be a sheriff.

Consider choosing somewhere new and fresh. I’m sure I’m not the only reader who has picked up a mystery novel simply because of the unique setting. The Shetland Island Mysteries by Ann Cleeves, and Tony Hillerman’s Leaphorn and Chee series spring to mind.

3. Pick a Sleuth

The plot and tone of your novel will depend on the who you choose to investigate the crime. Now that you understand genre, the sleuth may be a hard-boiled private investigator, a grizzled cop, or a spunky bookstore owner.

Make sure the sleuth has a strong reason to pursue the villain. I recently read a novel where the sleuth played cards with his friends and took his goddaughter to the zoo rather than investigating. His lack of focus and motivation might have been realistic, but it was maddening for the reader.

You also need to decide who will narrate. The story doesn’t always have to be told from the sleuth’s point of view. It can be told from the point of view of a sidekick (like Archie Goodwin in the Nero Wolfe mysteries) or from multiple points of view, like Robert Galbraith’s Cormoran Strike series.

4. Pick a Villain and Suspects

You will need a good villain (or villains), too. For the conflict to draw the reader in, the villain should have his or her own compelling story. The more conflicted and complicated the villain is the better, even if he or she doesn’t end up having much time on the page.

You’ll also need realistic suspects. The suspects may be completely innocent or can be villains of another story who just happened not to carry out this particular crime.

5. Write front to back or back to front?

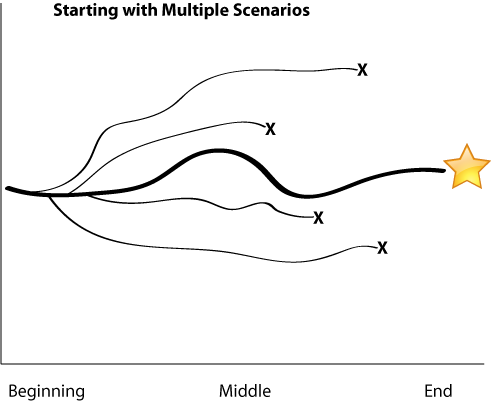

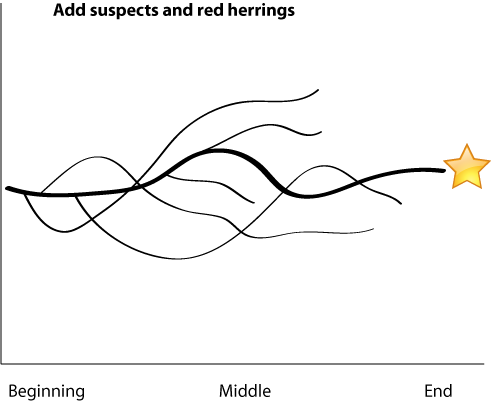

Plotting a mystery is complicated because the clues have to be laid out in the text so the reader can solve the main puzzle by the end of the book. On the other hand, to provide an enjoyable reading experience, the clues should not be obvious. Multiple solutions should be suggested, some of which are red herrings (clues that mislead the reader). How does a writer do this?

Because the crime is generally revealed in the first few pages, it is often easiest to start there. Develop an intriguing crime.

Front to Back (ending)

If you are a pantser and generally write from beginning to end, you might give yourself multiple scenarios of how it happened and who did it, and whittle them down to one at the end.

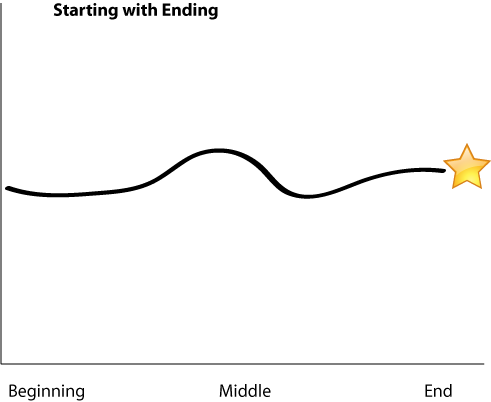

Back to Front

If you are a plotter, decide who did it and why (the ending). Construct a chain of clues to get you to that ending.

After laying out the main clues, build subplots around the trail of clues to obscure it. Point the reader in other directions. Leave out some clues and add others.

As you can see, both approaches lead to a similar structured mystery. Which works better for you will depend on how you organize your thoughts. Just don’t forget to maintain the suspense and have plenty of mini-cliffhangers at the end of each scene to keep the reader turning pages.

Note: Be sure to reveal all the suspects near the beginning of the story, if possible. Readers will toss your novel away in frustration if you bring the villain in on page 260.

How you physically record the plot details is up to you. Some people use index cards, some can’t live without software and spreadsheets, and others plan with sticky notes on a bulletin board. I personally use Scrivener because of the virtual index cards and outlining features.

The best method is what works for you.

Good luck!

Any questions? Let us know.