Now that we are working on scenes for our NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) prep series, let’s spend the next four days drilling into each of the components: description, action, dialogue, and thoughts/feelings. Since a new scene often starts with description, let’s tackle that first.

Description: The Definition

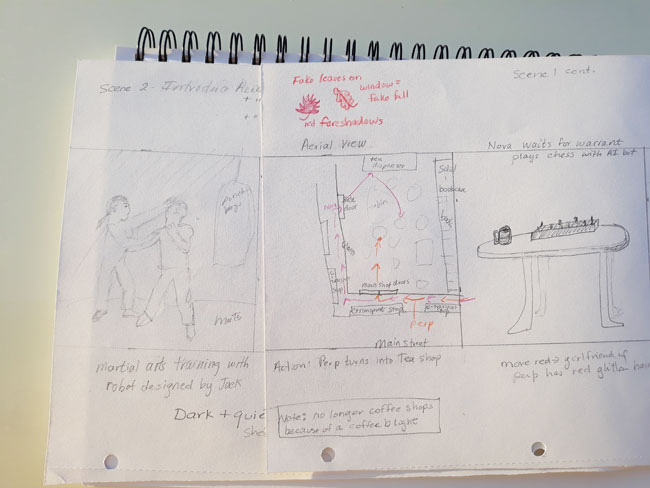

To make sure we’re all on the same page, the description component of a scene allows the reader to picture a place, person, or thing (or feeling) in their mind. Ideally, it should excite all the reader’s senses with concrete details. It is painting and sculpting with words.

How much description to include and when to include it will depend on genre and your personal style. The common advice is that a thriller will have a lot of action and little description, whereas a literary novel will often revel in description.

Examples

Regardless of genre, some writers make their descriptions sparkle. For example, in her essay, “The Map of How to Write,” Mary Sojourner uses description to take us on an intense emotional odyssey. Her personal style is to use amazing, surprising descriptions throughout her work.

“The sun is a platinum disc trapped in a web of dark branches on the surface of the water. A breeze moves over us. Sun and water-trees shudder.”

Typically, a mystery novel would have sparser descriptions, but ace novelist Raymond Chandler makes his descriptions into intriguing poetry. The beginning line of The Big Sleep:

“It was about eleven o’clock in the morning, mid October, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain in the clearness of the foothills. “

No cliché “It was a dark and stormy night…” for him.

The next paragraph describes the entrance to mansion he’s visiting.

“Over the entrance doors, which would have let in a troop of Indian elephants, there was a broad stained-glass panel showing a knight in dark armor rescuing a lady who was tied to a tree and didn’t have any clothes on but some long and convenient hair. The knight…was…not getting anywhere. I stood there and thought that if I lived in the house, I would sooner or later have to climb up and help him. He didn’t seem to be really trying.”

Although it seems like he’s engaging in some playful, offhand remarks, this paragraph mirrors later themes of his main character rescuing people in trouble. It is golden if your description can serve two –or more– purposes.

Upping Your Descriptive Writing Game

How do you write memorable, vivid descriptions?

1. Stomp out all clichés.

Instead of:

Shiny gemsArmed to the teethBlack as coalBird’s eye viewCrack of dawn

Try:

- Fish scales reflecting sparks of sun

- More weapons than brains

- An ebony cat on a moonless night

- Drone view

- Salmon pink glimmer at the horizon

2. Get into your character’s body and describe what he/she/they experiences through all their senses. Be as concrete as possible.

A character having a bad day at the gym:

Her leggings were too thick, trapping the heat of her body as she moved in rhythm with the rest of the class. Perspiration gathered at the small of her back and trickled across her skin. She caught a whiff of garlic and panicked that she smelled as bad as she felt, but it was the boy next to her. The ache in her head worsened as they spun left, then right. Where did her teacher get those hiccup sounds she called music, the bargain bin?

Revisit our post about setting in layers, which discusses what a given character will observe.

3. Don’t be afraid to pull out similes, metaphors and other literary devices. In the second Raymond Chandler example above, he used the personification of a stained glass window to great effect.

4. KISS: Keep it simple and keep it short.

We’re writers. We love words. As much fun as it is to write three paragraph descriptions, too much wordiness bogs readers down. If readers dislike the descriptions too much, they will start skipping those paragraphs and may miss out on some vital parts of your story. Write with your reader’s comfort in mind.

Exercise: Write a description of a place you enjoy visiting using all the senses you can pack in. Now pare it down to only a few sentences. What can be combined? What can be cut?

Share the result in the comments.

#####

Visit our 30 Day Novel Prep Page for all the links.