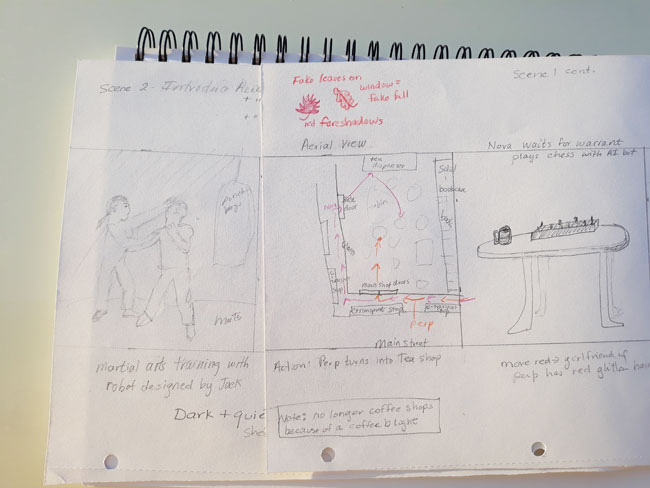

For our NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) prep series, we are drilling into each of the components of scenes: description, action, dialogue, and thoughts/feelings. Today let’s have a conversation about dialogue.

Dialogue is a verbal exchange between two or more characters in written format. We all know how to have a conversation, right? What possibly could go wrong?

Dialogue Dos and Don’ts

1. As with other components of your scene, make sure your dialogue serves at least one purpose. Keep these questions in mind:

- Is it revealing character?

- Illuminating the relationships between characters?

- Adding tension?

- Advancing the story?

2. Use proper punctuation and grammar. Dialogue has specific rules, such as where to place the commas, where to place the quotation marks, and how to use paragraph breaks.

For example, you should begin a new paragraph every time a new person starts speaking.

“It’s about your brother,” her mom said. Nova sighed. “What is it this time?”“Wasn’t his fault.”“Of course not. What happened?” Nova watched a young couple walk by, a golden retriever in tow. It tried to sniff her, but they yanked it away. “He had this one girlfriend. Rhonda. But then he got interested in another girl. A woman actually. A married woman.” Her mom was silent for a moment.“And?” Nova said, although she didn’t want to hear any more. “The woman got jealous of Rhonda. I think she knew he’d never be hers. Gees, she’s married. What’s she thinkin’?”Nova’s earpiece beeped. “Hold on, Mom. I’ve got an important communication coming in.”

Like this:

“It’s about your brother,” her mom said.

Nova sighed. “What is it this time?”

“Wasn’t his fault.”

“Of course not. What happened?” Nova watched a young couple walk by, a golden retriever in tow. It tried to sniff her, but they yanked it away.

“He had this one girlfriend. Rhonda. But then he got interested in another girl. A woman actually. A married woman.” Her mom was silent for a moment.

“And?” Nova said, although she didn’t want to hear any more.

“The woman got jealous of Rhonda. I think she knew he’d never be hers. Gees, she’s married. What’s she thinkin’?”

Nova’s earpiece beeped. “Hold on, Mom. I’ve got an important communication coming in.”

If you are unsure, there are many article and videos online to walk you through it.

3. Real people don’t all sound alike. Give your main characters differences in their speech patterns. It will make your dialogue more interesting, plus you’ll be able to get away with using fewer dialogue tags because readers will be able to tell them apart more easily.

Do you hear the subtle differences in speech between Nova and her mother above? Nova’s mom is less formal and uses more contractions.

J.K. Rowling gives her character Hagrid a distinctive voice.

“Well, yeh might’ve bent a few rules, Harry, bu’ yeh’re all righ’ really, aren’ you?”

4. On the other hand, don’t go overboard with unusual accents. Uncommon accents can be hard to decipher and can pull a reader out of the story. If one of your characters is from an area known for a strong regional accent, it may be possible to use it moderately at first to suggest the sound to the reader and then subtly back away.

5. Use dialogue tags and action beats to avoid “talking heads”.

Dialogue tags are the words that tell the reader who is speaking and how. Action beats are short sentences that come before, between, or after dialogue. They tell us more about what the character is doing, feeling, or thinking. In the quote below, the dialogue tags are marked in red, the action beats in blue.

“You take the bus?” Nicky asked.

Lauren’s perfect posture slumped a tiny bit. “My parents took away my car.”

“Bummer.” Nicky wasn’t surprised. Lauren did have a reputation. “Why don’t you get one of those ride services?”

“They took my phone and allowance, too.”

“That sucks,” Nicky said.

Lauren’s manicured eyebrow twitched as she studied Nicky for signs she was making fun. Apparently appeased, she said, “Tell me about it. I hate my parents. They’re never there when I need them, only when I don’t want them.”

6. Mix things up from scene to scene.

It can be easy to fall into a rut when writing dialogue. You might do exactly what you did in the last scene, which can get repetitive and boring for the reader. You can change:

- The amount of dialogue you include per scene — shorter is better.

- How you break the dialogue up on the page.

- Up the tension between characters

- Use more subtext (what is being left unsaid)

- Cut small talk or greetings/goodbyes

- Change the pace. Use short sentences in an action scene, longer sentences when one character meets another for a first date.

A great video about subtext

7. Avoid “on the nose” dialogue, which is stating the glaringly obvious.

Example:

“I’m really sad my cat died.”

In fact, most people are more likely to withhold information during a conversation than overshare. Play with that instead.

8. Also avoid “maid and butler” dialogue, aka “as you know.”

Sometimes an author needs to explain something to the reader that the main characters would already know, such as how to use a specialized piece of equipment, what happened at a party last week, or what the effects of a certain disease might be. For example, avoid having one doctor say to another, “As you know, Bob, diabetes can cause eye damage.” Instead, have the doctor explain the details to a patient (or medical student) and allow the patient to ask questions as a stand in for readers.

All in all, don’t get too caught up in the dos and don’ts. Writing dialogue can be a fun change of pace.

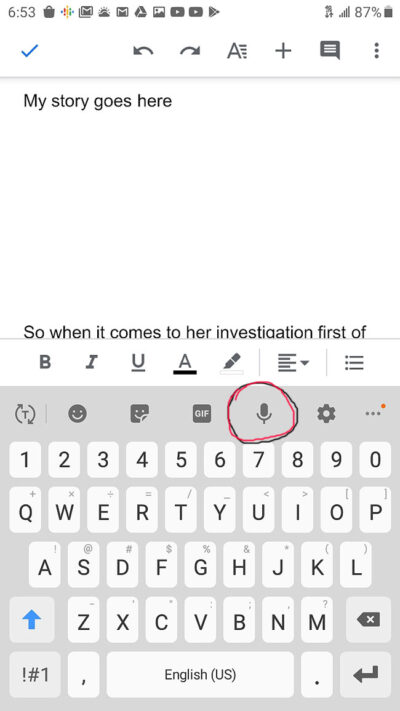

Exercise: As a way to discover how much you can actually leave out of dialogue and have it still make sense, try this modified version of an exercise from Writing Excuses podcast: Either take dialogue that you’ve already written or write a scene that is heavy with dialogue, then remove every third line. Does it still make sense? Can you fix any problems with an action beat or two?

Do you enjoy writing dialogue?

#####

Visit our 30 Day Novel Prep Page for all the links.