In our final post about setting for NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) preparation, let’s discuss how to show setting in your novel.

Setting is something that you should reveal early in the novel, preferably on the first page or even along with your character in the first few sentences. How you do so will depend on your character’s familiarity with their surroundings and what tone/mood you want to convey.

Setting in Layers

We haven’t discussed point of view yet, but it pays to keep it in mind when considering how to include setting.

Did you look into the Onion Theory of Characters from our previous post on protagonists? In review, the idea is that how someone describes someone else depends on their relationship. If one person sees another in a store that she doesn’t know, she will describe that person superficially, that is by what they look like, what they are wearing, etc. A colleague will understand more about a character, such as where they went to school, what kind of car they drive, and how often they are late to work. A character’s mom, on the other hand, can reveal truly deep and hidden things about them. So, the longer they know someone, the deeper their understanding goes.

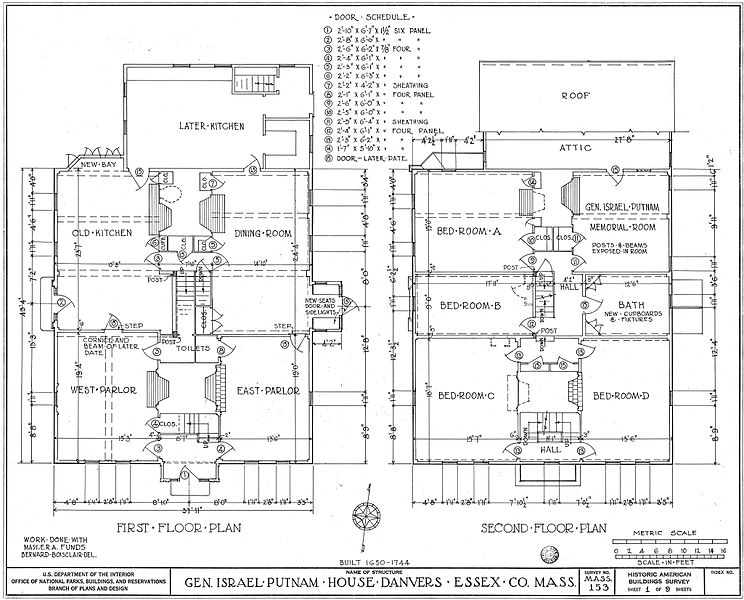

I recently read the novel Devices and Desires by P. D. James and realized someone’s relationship with setting will lead to the opposite in terms of description. In her book, the protagonist Commander Adam Dalgliesh is visiting the Norfolk coast to settle his aunt’s estate. Because he just arrived, he notices many things with fresh eyes. He looks out the window and describes the surrounding land and the houses of his neighbors in detail. Another character, who has been there a bit over a year, notices the things that are different or what has changed since last time she looked. The characters who have lived there forever hardly notice the setting at all. Yes, they know the setting intimately, but they don’t register it as a newcomer would.

How do you use this revelation?

If your character is in a familiar place, consider what they might notice. They would probably note the lighting, which changes daily and possibly the temperature of the room. They would definitely look at the new piece of art they put up the day before or the bulletin board they cleaned off. Maybe they would register the smell of cleaning supplies if they cleaned the bathroom or the lingering odor of the garlic bread from lunch. The bottom line is that they would pay attention to the things new or different from the day before.

What do you do if you need a deeper description of a place than your main character would realistically supply?

1. Create a character who has never visited the setting you want to describe. You don’t necessarily have write the scene from their point of view, but you can have the novice character ask about things she or he sees or hears, bringing the setting into a conversation.

Example: In a recent television series, the protagonist invited a woman to his apartment for the first time. She immediately commented on the flashing neon sign outside the window, which he didn’t even register. He explained that was why his rent was so cheap, revealing something about his economic status.

2. Have your main character have a flashback, allowing them to describe a scene from when they might have first encountered it, as well as the emotions linked to the events that happened at that time.

“He remembered it from his childhood…on those long dark afternoons in winter before the Sunday school was released, when the outside light was fading and the small Adam Dalgliesh was already dreading those last twenty yards of his walk home, where the rectory drive curved and the bushes grew thickest. Night was different from bright day, smelled different, sounded different; ordinary things assumed different shapes; an alien and more sinister power ruled the night. Those twenty yards of crunching gravel, where the lights of the house were momentarily screened, were a weekly horror.”

As you might suspect, the chilling fear this passage evokes has to do with other things that are going on in the story, namely some grisly murders. Adult Adam would not express those feelings, but childhood Adam could.

Exercise:

Go to a familiar place that might serve as a setting for your novel. Spend some time taking in the details, making sure to consider all the senses. Write down what you notice first, second, third. Describe the place. How does it make you feel?

Now, if possible, visit a place you’ve never been before. Again, look, listen, smell, touch. What do you notice first, second, third? Write a description. Include how the new place makes you feel.

Go back to your notes a few days later. Do you notice and similarities in how you described the places? How about differences?

Tip: If you are writing science, speculative, historical fiction or fantasy, Writing Excuses podcasts has a slew of information about world building. Unfortunately the episodes are listed under two separate tags which will give you different resullts: Worldbuilding (one word) and World Building (two words).

For example, for historical, one episode gives a great suggestion of printing out a calendar from the year your novel is set in order to develop your timeline. Yes, there are old calendars online.

#####

Visit our 30 Day Novel Prep Page for all the links.