Before we move on from plot and structure, let’s consider adding a subplot or two.

What is a subplot?

A subplot is a secondary or side story that supports the main plot.

Why Add Subplots?

Subplots can serve a couple different purposes, but the main one is to add depth and interest to a novel.

Subplots:

- Reveal more about primary and secondary characters, making them more three-dimensional

- Provide times of reflection or comic relief

- Can drive certain plot points

- Supply conflict or complications to test the main character

- Are a way to show backstory organically

Example:

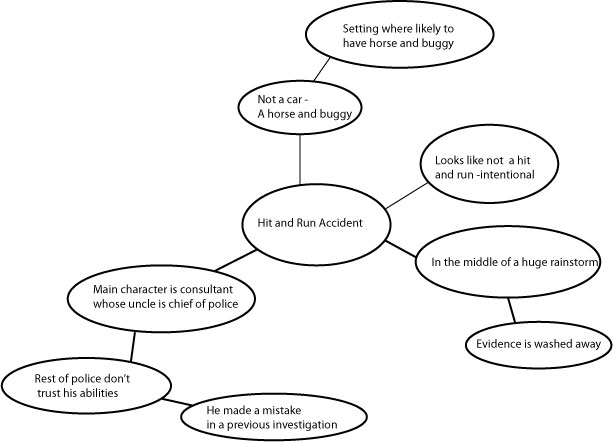

Let’s go back to the premise we created in the first post:

When he’s called in to investigate a hit-and-run accident, expert consultant John Smith discovers the death is intentional. He must find out the victim’s identity before the murderer strikes again.

One of the side branches of the mind map revealed that John Smith was called in because his uncle is the chief of police. A subplot might be that John’s uncle wants him to say the crash was an accident. Before long, John’s mom asks him to come to a family dinner. John knows it is a ploy to get him to listen to his uncle. John makes an excuse and dodges the dinner by going to question a witness.

This subplot serves multiple purposes. It adds tension. It shows John tends to avoid conflict, thus revealing his character. It also strengthens his resolve to prove his uncle wrong.

Maybe his mom tries to get him to come to dinner again later in the story to keep the subplot going, revealing more.

Some Subplots to Consider

1. Drama with Protagonist’s Day Job

My protagonist is an amateur sleuth trying to solve a crime. I’m going to have her unrelated day job get in the way.

Think of all the times school work interferes with Harry Potter’s progress toward his goal.

2. Romantic Interest

Your protagonist’s love life can either offer relief from the main plot’s tension or make them vulnerable (be a test).

3. Health Issues

I recently read a novel with a pregnant protagonist. The subplot included visits to various doctors and conflict with the baby daddy, both which slowed down her progress and increased tension.

4. Family

Thank goodness for family to add complexity to any story. Janet Evanovich’s Stephanie Plum character has an eccentric family that offers comic relief after she has a hard day battling bad guys.

Family can also drive plot points. In Pride and Prejudice, when Elizabeth’s sister runs off with an illicit lover, Darcy, who Elizabeth has previously spurned, comes to her rescue. This changes Elizabeth’s perception of Darcy and moves the plot toward resolution.

5. Past Trauma

Was your main character a victim? Do they have fears or emotional scars that make them vulnerable or hobble their ability to accomplish their goal?

Exercise

Look through your list of secondary characters. Do any have the possibility of being developed into a subplot? How can they add to the main plot?

If you don’t have any likely candidates, consider adding secondary characters who would drive a subplot, such as coworkers at their day job or a psychologist your protagonist visits to discuss his/her/their past trauma.

Don’t be afraid to have more than one subplot. Harry Potter has not only his teachers and school work to consider, but also his past trauma of losing his parents.

Are you going to include a subplot in your NaNoWriMo novel?

#####

Visit our 30 Day Novel Prep Page for all the links.